Years of over confidence in technological superiority and analytical expertise had fostered a dangerous complacency.

By Hezy Laing

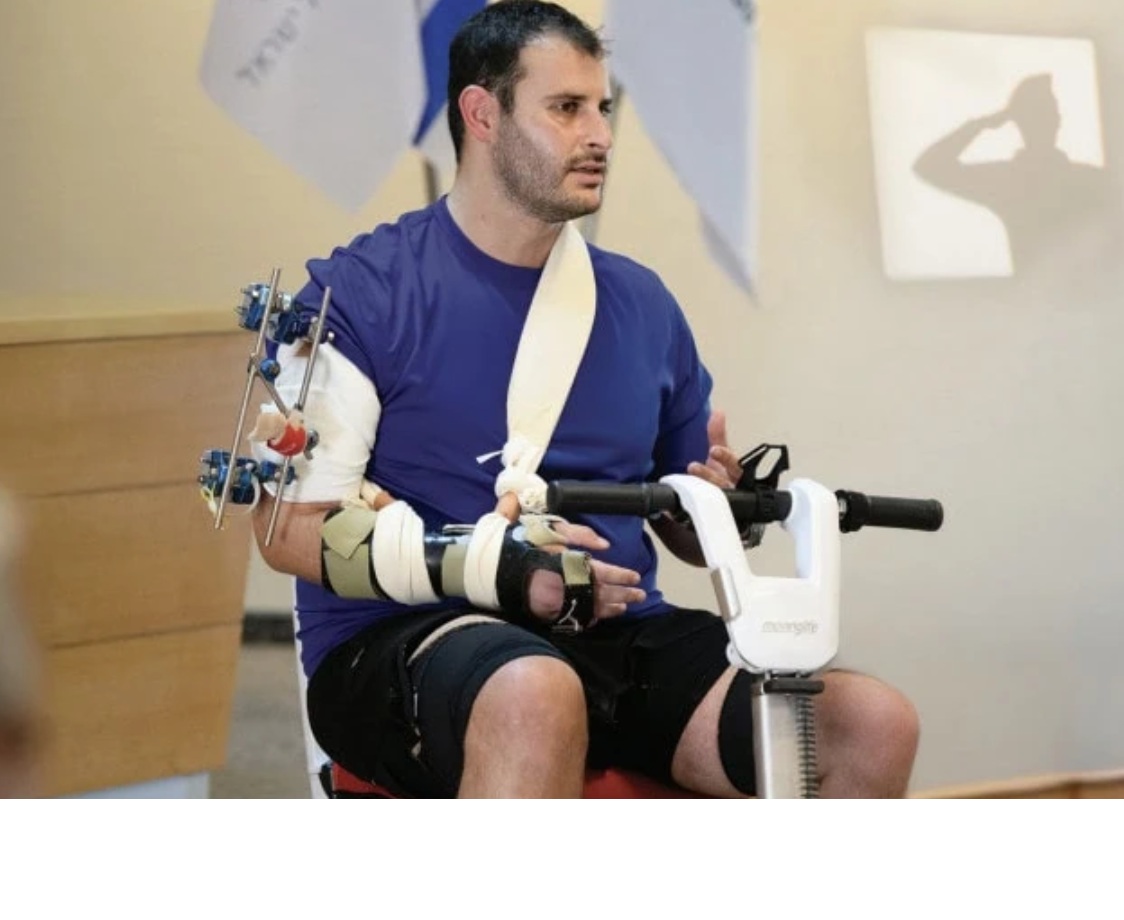

For nearly three decades, Guy Itzhaki lived at the heart of Israel’s defense establishment.

A decorated intelligence officer, he fought in the Second Lebanon War, exposed Hezbollah tunnels, tracked Iranian arms smuggling, and even served as assistant to Chief of Staff Benny Gantz.

He lectured internationally on counterterrorism and authored a book on Hezbollah.

By all accounts, Guy had seen everything.

Yet on October 7, 2023, his world collapsed.

Waking at dawn with a sense of dread, he soon realized Hamas had launched a massive assault.

Within hours, he was at headquarters, watching footage of militants roaming freely through Israeli towns.

“It felt like the Yom Kippur War all over again,” he recalled.

His unit, responsible for documenting enemy tactics, quickly became the central hub for evidence of the massacre.

Over the next months, Guy reviewed five terabytes of raw footage—terrorists’ GoPro videos, phone recordings, and security camera captures.

But nothing prepared him for visiting Kfar Aza and Be’eri days later.

“It wasn’t a death camp—it was hell on earth,” he said, describing bodies strewn across homes and streets.

That night, he broke down in tears.

Diagnosed with PTSD, Guy realized something inside him had shattered.

The tragedy was compounded by the failure of Israel’s intelligence community to foresee the attack.

Years of over confidence in technological superiority and analytical expertise had fostered a dangerous complacency.

“Ego is the enemy,” Guy reflected.

The arrogance of seasoned experts blinded them to the many warning signs, leaving the nation exposed when vigilance was most needed.

After decades of service, Guy retired from the army, expecting rest and family time.

Instead, he faced emptiness.

“For the first time, I came home without responsibility, and I was broken,” he admitted.

Then, a small discovery changed everything.

Searching his closet, he found the tallit and tefillin gifted by his father‑in‑law years earlier.

Though he had rarely used them, something compelled him to reach out to his rabbi brother‑in‑law for guidance.

“I think God saw me at my lowest and helped me get up,” Guy reflected.

That single act became the first step in a spiritual journey.

He began praying daily, reciting Psalms, and slowly attending synagogue.

At first, he feared criticism, but instead found warmth and belonging.

“I found a beautiful community. I felt at home.”

He immersed himself in Jewish texts—Ecclesiastes, the Talmud, and The Paths of the Just—seeking truth and meaning.

He started keeping Shabbat, despite the challenges of quiet reflection with PTSD.

“Shabbat is time for me to arrange my thoughts, to think more, to do less,” he explained.

His wife, Anat, and their daughters gradually joined him in exploring Judaism, each at their own pace.

Guy’s trauma remains.

He avoids television, struggles with sleep, and feels guilt over October 7.

“There isn’t an hour when I stop thinking about what I saw,” he admitted.

Yet his connection with God sustains him.

“Besides my wife and girls, this process with God is maybe the best thing I have. It gave me meaning, answers, and keeps me alive mentally.”

He acknowledges that ego once defined his military career.

“I thought the story was about me. Now I understand it’s about me and Him, about becoming a better person.”

[From an article originally published by Aish.com]